Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York

Curated by Julia Foulkes

NY Public Library for the Performing Arts

Sept. 26, 2018–March 30, 2019

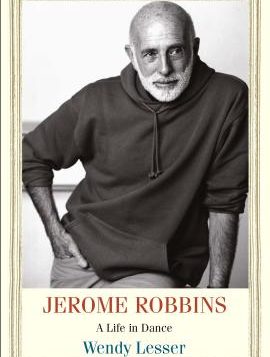

Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance

Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance

by Wendy Lesser

Yale Univ. Press, 200 pages, $26.

LAST YEAR marked the centennial of the birth of acclaimed dancer and choreographer Jerome Robbins (1918-1998). To commemorate this anniversary, two separate tributes warrant our attention: Wendy Lesser’s biography Jerome Robbins: A Life in Dance and the retrospective exhibition Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York.

Wendy Lesser, founder and editor of The Threepenny Review, has written a brief and engaging biography of Robbins that draws factual information about his life from biographies by Deborah Jowitt (Jerome Robbins, 2004) and Amanda Vaill (Somewhere: The Life of Jerome Robbins, 2006). Lesser provides just enough new information to enhance our understanding of the choreographer and the man. She offers a detailed analysis of his works as an entrée into his psyche. Each chapter focuses on a phase in his life and indicates how his choreographic efforts were interwoven with his life and his interior world. Robbins’ immense œuvre included such ballets as Age of Anxiety, The Cage, Dances at a Gathering, Afternoon of a Faun, The Goldberg Variations, In Memory of, and the unfinished Poppa Piece; as well as the Broadway musicals Fancy Free, On the Town, The King and I, Peter Pan, West Side Story, and Gypsy.

Lesser presents Robbins as a complicated person who struggled with inner conflicts involving his perfectionism and drivennes, his family, his Jewish identity, and his sexuality. His life became more complicated when he was summoned to testify before the House Un-American Affairs Committee in 1953. Threatened with public exposure if he didn’t “name names,” he feared that his career would be ruined if he didn’t testify, and so he did, naming some individuals as Communist sympathizers. For the rest of his life, he was tormented by this betrayal of colleagues and friends.

Lesser also discusses Robbins’ sexuality, which included sexual relations with both women and men. His most passionate relationship was perhaps with the (female) ballet dancer Tanaquil Le Clerq. His affairs with men tended to last longer than those with women. Still, he sometimes lamented that he couldn’t sustain a lasting relationship with either sex, and this bothered him throughout his life.

Lesser also discusses Robbins’ sexuality, which included sexual relations with both women and men. His most passionate relationship was perhaps with the (female) ballet dancer Tanaquil Le Clerq. His affairs with men tended to last longer than those with women. Still, he sometimes lamented that he couldn’t sustain a lasting relationship with either sex, and this bothered him throughout his life.

Further insights into Robbins’ career are offered by the exhibition Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York, a retrospective that’s a celebration of his life. He drew inspiration from New York City and its ever-changing landscape. The exhibit follows Robbins’ evolution as a dancer and choreographer through photos, videos, diaries, poems, personal papers, and artwork that give us a window into his imagined world. It moves through Robbins’ ballets and musicals with rooms showing scenes from some of his biggest hits, including the shows mentioned above along with Fiddler on The Roof, NY Export: Opus Jazz, Glass Pieces, and many more. One memorable room contains his journals, which are elaborately festooned with theater memorabilia, ticket stubs, drawings, photos, dried flowers, quotations, and his own introspective writings.

Like Lesser’s biography, the exhibit addresses Robbins’ psychological conflicts involving his family, his Jewish heritage, the HUAC testimony, and his gayness. At the entrance to the exhibit are two drawings by Robbins that contain within the frame the two quotations “Why can’t people just accept you?” and “If only they’d leave me alone.” In one of the rooms there’s a large canvas that fills almost half the space: a vast assortment of images that Robbins pieced together and the following quotation, taken from his Diaries 1971–1984: “I’m afraid I’ll be found out … but what will be found out?”

Robbins’ final theatrical work, The Poppa Piece, is mentioned by Lesser and alluded to in the exhibit. Robbins began it in the early 1990s but never finished the work. He titled it The Trial, which he associated with the theme of betrayal. Many of the images in this work relate to his relationship with his father as well as his feelings of guilt and betrayal over the HUAC testimony, his conflicted identities, masculinity, and repressed memories from his earlier life. Unfortunately, he never finished the piece.

Irene Javors is a regular contributor to this magazine.